The inspection of high-pressure turbines (HPT) is one of the most laborious yet crucial tasks in maintaining an aircraft jet engine.

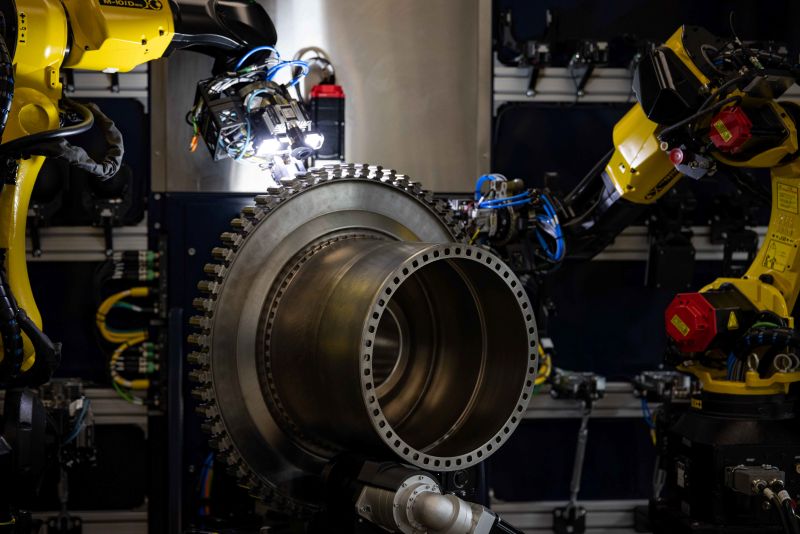

Every nook and cranny of the HPT is examined. In particular, the precisely machined, nickel-based disks that bear the blades of the HPT are painstakingly scrutinized as part of their maintenance. Even the most minor anomaly — a scratch or a minuscule smudge of corrosion — requires professional judgment on whether the part should be accepted, repaired, or rejected.

To reduce the time this inspection takes, engineers at GE Aerospace Research in Niskayuna, New York, and GE Aerospace’s Global Automation and Robotics Center in Bromont, Quebec, spent five years developing robotic inspectors to assist the process.

The first AI-guided “white light robot” inspectors were deployed in the maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) shop at the Services Technology Acceleration Center (STAC) in 2024.

The below article takes a closer look at the white light robots in action.

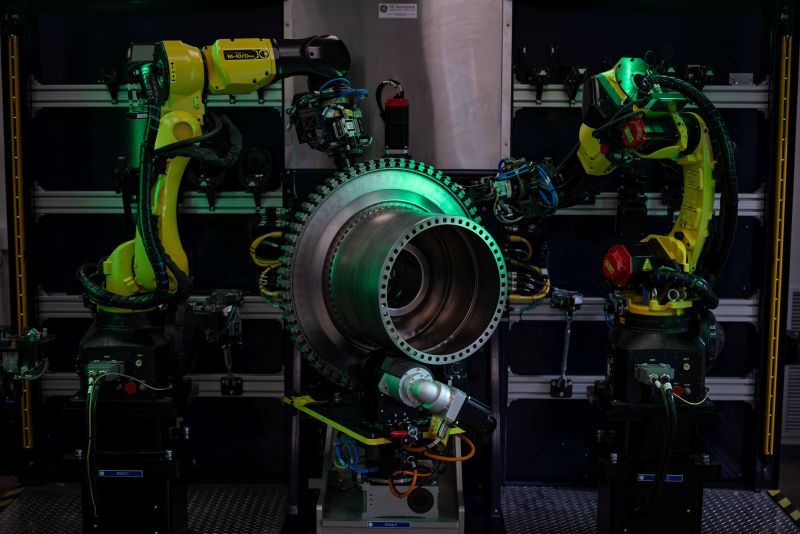

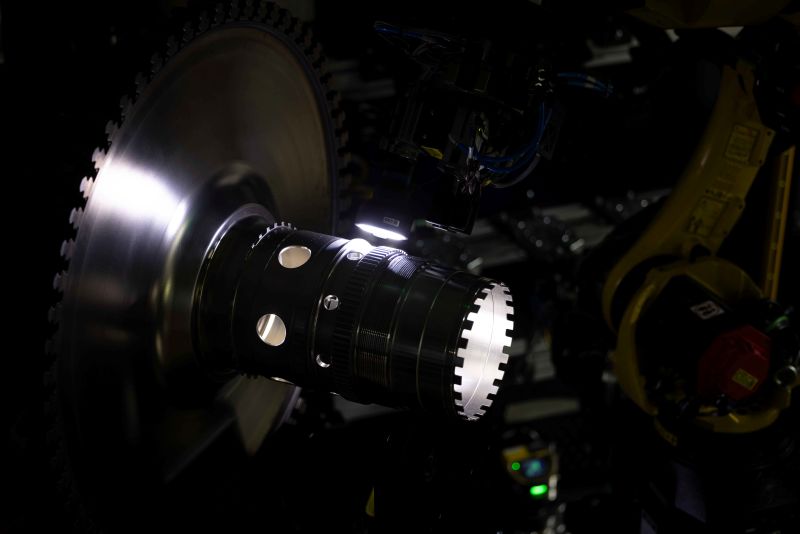

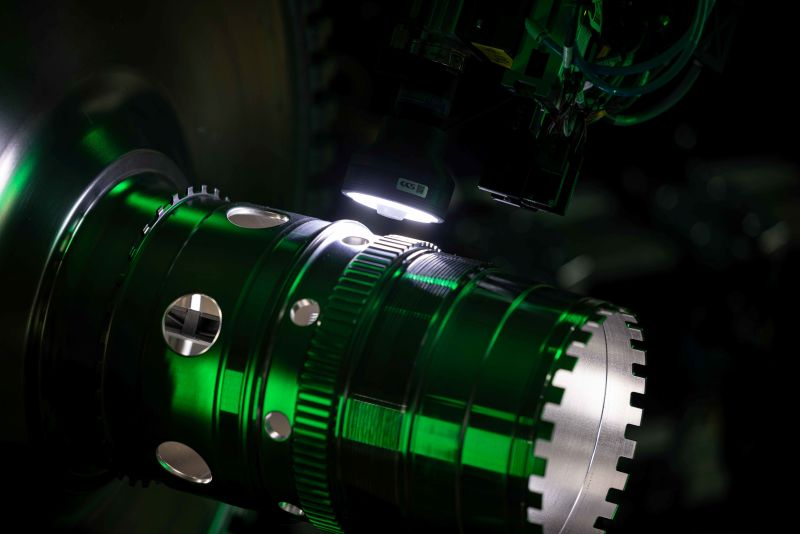

Standing in a universal workstation, two articulated industrial robots outfitted with white light optical scanners move closely over the entire surface of the high-precision part — in this case, a turbine disk for a GE90 engine. Like two ballroom dancers, the robots’ movements are carefully choreographed by human operators and use AI to capture and analyze data with optimal accuracy, speed, and consistency, simultaneously creating a digital record of each part’s condition.

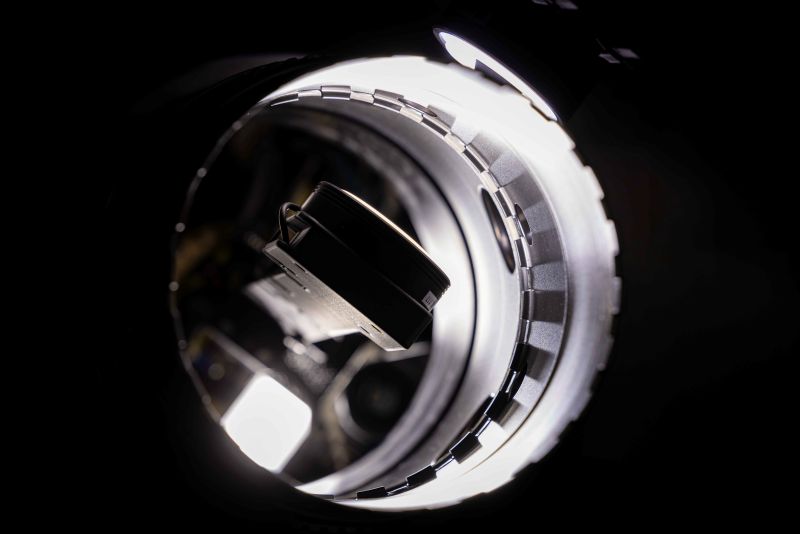

“Staring at the same part or feature for eight to twelve hours a day can make your head hurt,” says Sam Blazek, GE Aerospace services technology leader for white light inspection, who in the past inspected parts by hand, with a flashlight and a mirror. “You’re constantly twisting your head, eyes, and neck as you try to focus on each individual feature.” The robot inspector slips right into the disk’s interior.

By performing each inspection on a standard digital platform, white light robots ensure a consistent flow of extremely fine-grained information. They record the part’s serial number, assign a numerical value to any anomaly whether dent, crack, corrosion, or fretting and develop a consistent chronological narrative of the part that is instantly accessible in the cloud, indicating where repairs might make a part serviceable and providing a complete record of non-serviceable flaws.

The first generation of white light robot technology captured images and digitally stitched them together. But line-scan cameras developed at GE Aerospace Research provide a higher-quality, video-like stream that replicates what a human eye can see, displayed on a computer monitor.

White light robot inspection reduces the noise from variations between human inspectors, whom it will also help to train. Rather than rely on predictions or simulations of likely wear and tear on a life-limited part (LLP), the collective data provides high-resolution information about the actual part.

Once programmed and activated, the system doesn’t need to be monitored for its entire operation time. “The goal is to mount a part for inspection, hit ‘go,’ let the system run while you go do another job, and come back to monitor the inspection on a screen,” says Blazek. “A person still needs to be there to examine the screen and make the call. They just don’t need to physically huddle around the part for hours on end to collect the data. We use their expertise where it’s needed, which is in disposition.”

When Blazek joined the team at STAC, his deep domain expertise helped in the development of policies and procedures that, along with AI’s sophisticated data storage, make it possible to scale and produce the second-gen system. “We’re not trying to replace humans with this technology,” Blazek says. “We want to replicate them. If we can automate some of the ‘easier’ repeatable, predictable aspects of this job, it frees our inspectors to focus on the technical issues that truly need our attention.”

This article was written by Chris Norris and originally published by GE Aerospace. It can be viewed in its original version here.